Dr. Troy Vander Molen, PT, DPT

As a senior in high school, I, like many students, applied to several colleges and filled out a number of scholarship applications. After receiving my application, one college in particular invited me to campus to engage in a personal interview for one of their larger academic scholarships, so I packed my nicest clothes, got in the car with my parents, and drove for five hours to their pristine campus, not knowing exactly what to expect.

The scholarship for which I was being considered was named after Norman Vincent Peale, an American minister and author who is known for his work in popularizing the concept of positive thinking. In fact, he authored a best-selling book entitled The Power of Positive Thinking, which no doubt influenced the Reverend Robert Schuller, pastor at the popular Crystal Cathedral in southern California that launched the televangelism movement in America. So, as I made the trek seeking this distinguished opportunity, I, like Peale and Schuller, maintained great optimism though I had never participated in a personal interview in my short life.

As I met and talked with the interviewers, our conversation centered around my family, my academic and extracurricular experiences, and my belief system. At one point, one interviewer asked, “Who are a few of your heroes?”

I suppose I should have been prepared for such a question, but I was not. I gave the patented answer: my parents. I spoke about my love of baseball and my favorite Kansas City Royal player, George Brett. And I mentioned my new-found respect for Martin Luther King, Jr. having recently read his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, which he penned 27 years earlier in April of 1963.

The interviewers looked somewhat perplexed with my response. I was meeting with them in a small, rural town in northwest Iowa where many people worshipped in a Reformed or Christian Reformed church. Maybe they thought I was speaking about Martin Luther, not his namesake of this Protestant reformer, the Black minister and racial activist from Atlanta. Or perhaps they didn’t expect a Caucasian teenager from a predominantly white community in a small Midwestern town, someone who was born nearly a decade after the events in Birmingham and several years following his assassination in Memphis, to put MLK on his Mount Rushmore of Heroes.

When asked why I considered Martin Luther King, Jr. a hero, I mentioned that I was amazed at how he truly understood the human condition and was willing to stand for truth and justice while also maintaining his Biblical convictions. The fact that he used his platform to stand between two forces, one of complacency and another of bitterness and hatred, and model the “more excellent way of love” was impactful to me.

It has been many years since I read MLK’s letter in its entirety, so I reread this message to his fellow clergymen this past weekend in advance of today’s celebration of his life. I would encourage you to do the same for you may find, like me, that his words are as timely today as they were then.

In the middle of his address, this excerpt rings in my ears:

Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

This quotation was offered in the context of what King considered his people’s “great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom… the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice…”

King emphasized that the presence of tension was not the result of the Black people who had committed to “nonviolent direct action” but instead stressed that these people “merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive.”

When Colin Kaepernick knelt as a protest to the national anthem in 2016, an act that started a movement in the NFL and stoked emotional responses across our country, my response was typical of a member of the predominant race in America. “I understand his concerns, but this is not the time or place.”

In his 1963 letter, King’s words have helped me understand the foolishness of that type of thinking. He emphasized the importance of shining the light on prejudice, and he underscored that the status quo will not change, that growth will not occur, without “constructive, nonviolent tension.” Much of King’s letter is a warning and admonishment to the Christian Church for having ignored this reality and, by its silence, becoming an “arch defender of the status quo.” And he encouraged the readers to use their time creatively “in the knowledge that the time is always ripe to do right.”

I think the reason I am most enamored by Martin Luther King, Jr. is that, despite the injustice that he both witnessed and personally experienced, he never became bitter and always remained hope-filled. In the manner of Norman Vincent Peale’s exhortations, King remained optimistic by clinging to the principles upon which the Church was founded and upon which the United States of America was established. He maintained hope for the future despite the depravity of man and its sin-impacted institutions, which he emphasized in this portion of his letter:

But even if the church does not come to the aid of justice, I have no despair about the future. I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham, even if our motives are at present misunderstood. We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with America’s destiny. Before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson etched the majestic words of the Declaration of Independence across the pages of history, we were here.

A core premise of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s approach to bringing about justice is one that we are wise to remember and highlight this MLK Day and always, and it is this: While tension is necessary, violence is not acceptable. King outlines that an effective, nonviolent campaign requires “four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action.”

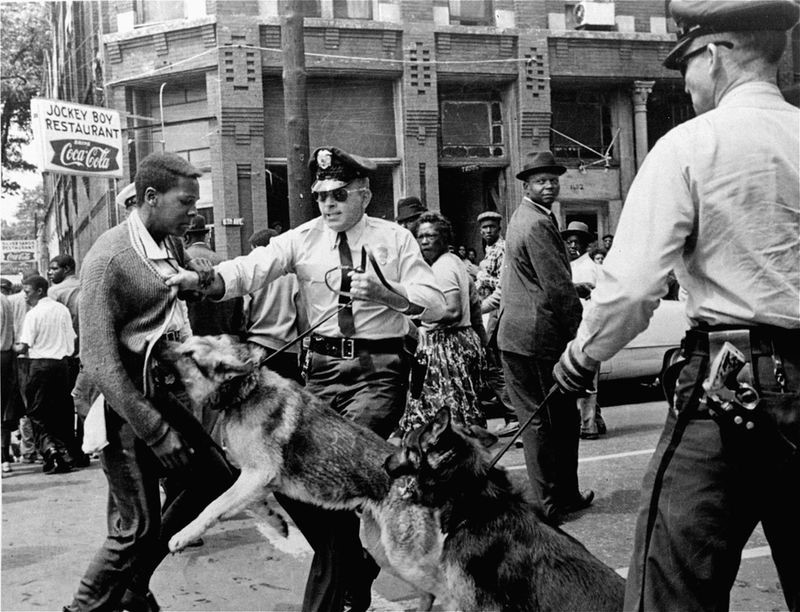

Throughout his life as a minister and leader, he remained true to these Biblical values, and he changed the world. I cannot fully appreciate what is like to be a Black person in America, then or now, but I know that it is extremely difficult to see what he witnessed, to experience what he experienced (see the photos at the end of this story the “riots” in Birmingham) and remain committed to purification of self. In fact, while challenging the status quo, he also chastised some of those within this movement, “people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incorrigible ‘devil.’”

It was hard enough for me to forgive the interviewers who decided to award the Norman Vincent Peale Scholarship to another candidate instead of me, but, unlike me, King was absolutely committed to his core beliefs, the Biblical truths that he, a son and grandson of a generation of ministers of the Gospel, learned from his ancestors. Perhaps I should have taken on the mind of MLK he modeled when he penned the following in the closing of his letter:

If I have said anything in this letter that overstates the truth and indicates an unreasonable impatience, I beg you to forgive me. If I have said anything that understates the truth and indicates my having a patience that allows me to settle for anything less than brotherhood, I beg God to forgive me.

I will learn from my mistakes and take on that approach today. May the words and witness of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Truths upon which his beliefs were formed, be my and your guide as we remember and reflect this MLK Day.